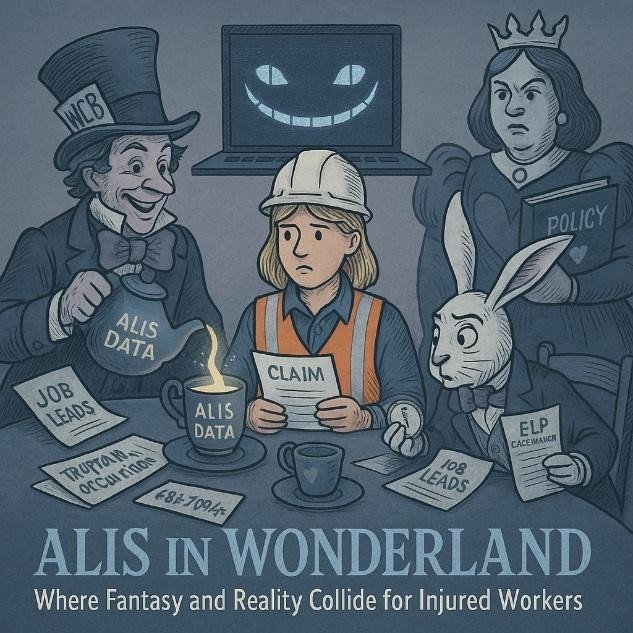

When an injured worker can no longer return to their pre-accident trade, the Workers’ Compensation Board steps in to determine what they can reasonably earn in a new occupation. That determination—known as Earning Capacity—is the cornerstone for calculating long-term benefits such as Economic Loss Payments (ELP) and wage supplements (“top-ups”).

In principle, this process should be rooted in realism. The law and WCB policy both require decisions to reflect what a worker can actually earn in the competitive labour market, not what they might earn in theory. Yet in recent years, the Board’s vocational system has drifted from reality toward abstraction, relying less on human investigation and more on a government database called ALIS.

It is a shift that has quietly transformed how injured workers’ earning capacities are calculated, and not for the better.

What ALIS Is (and Isn’t)

ALIS, short for Alberta Learning Information Service, is a publicly funded career and education database managed by the Government of Alberta. It’s designed as a career-exploration tool, not an adjudicative instrument. It provides general information about occupations in Alberta: job descriptions, typical wages, education requirements, and physical demands.

In high-school guidance offices and employment-counselling centres, ALIS is a helpful resource. It allows job seekers to explore careers, compare salaries, and understand what training is required for different roles. But it was never meant to determine someone’s earning capacity in a legal or compensation context.

Each ALIS occupation profile is built on aggregated data from labour surveys, census statistics, and National Occupational Classification (NOC) codes. It paints an average picture of a job, but not the nuances of specific employers, hiring practices, or local labour markets. It assumes access to training, experience, and opportunity.

How WCB Uses ALIS

Within WCB Alberta, ALIS now underpins the work of Re-employment Specialists (RES) in the Re-employment Services Department, the branch responsible for helping injured workers transition back to suitable employment.

When a worker’s medical restrictions are declared permanent, the RES team conducts what is called a Labour Market Analysis (LMA) to identify potential occupations that meet two criteria:

- Physically suitable given the worker’s restrictions, and

- Vocationally attainable based on education and experience.

At least, that’s how it’s supposed to work.

Before 2020, LMAs involved direct employer outreach. Re-employment Specialists phoned hiring managers, spoke to human-resources staff, and confirmed whether an injured worker with certain restrictions could actually perform a given job. They verified wage ranges and ensured that the role existed in the worker’s geographic region.

Those outreach notes became the backbone of vocational realism—bridging the gap between policy and practice.

The Post-COVID Shift: From Employers to Algorithms

When COVID-19 disrupted in-person operations, WCB suspended field outreach. The Re-employment Services team pivoted to a “desk-based” model, using ALIS as the default source of labour-market information.

What began as a temporary measure has now become permanent practice. Today, LMAs are often generated entirely from ALIS data, without a single phone call to an employer.

This has fundamentally altered the nature of vocational adjudication:

| Pre-COVID (Traditional LMA) | Post-COVID (ALIS-based LMA) |

| Direct contact with employers and HR departments. | No outreach; relies exclusively on database averages. |

| Regional wage verification and job-availability mapping. | Province-wide or generalized wage data detached from location. |

| Customized analysis of skills transferability. | Template-based assumptions of transferability via NOC alignment. |

| Evidence grounded in real-world hiring practices. | Evidence derived from generic, static occupational summaries. |

In essence, a process once rooted in reality testing has devolved into data fitting.

The ALIS Reliance Problem

ALIS assumes a level playing field—where every worker has equal access to education, technology, and retraining. But WCB’s mandate is to deal with workers as they actually are, not as they appear in aggregate data.

By lifting occupational titles straight from ALIS, Re-employment Specialists can populate a worker’s “suitable occupation list” without ever confirming that such jobs are attainable for that individual. The problem is structural:

1. Physical ≠ Vocational Suitability

ALIS describes only physical demand levels (sedentary, light, medium, heavy). WCB interprets “light” or “sedentary” as suitable for anyone with restrictions, even when the job requires advanced administrative or technical competencies.

2. Statistical ≠ Realistic Wages

ALIS wage data reflects averages across entire industries and regions. A worker re-entering the labour market after a disabling injury rarely starts at the statistical average. Yet WCB imputes full-scale earnings from day one, artificially shrinking or eliminating wage-loss benefits.

3. Generic ≠ Individualized Assessment

Policy 04-04 explicitly requires that earning capacity decisions account for the worker’s age, education, training, and experience. ALIS accounts for none of these.

Who Uses ALIS Inside WCB

ALIS is primarily used by Re-employment Specialists (RES) within WCB’s Re-employment Services Division. These are the professionals tasked with bridging the medical and vocational gap once an injury stabilizes.

They create job leads, estimate wages, and make recommendations that directly affect how much a worker will receive in long-term benefits.

In theory, RES specialists should conduct individual vocational assessments. In practice, workload pressures and institutional policy have shifted their function from field investigators to database operators. They now input restrictions and prior occupations into an internal matching tool, which cross-references ALIS codes to generate potential “suitable occupations.”

Once those occupations are listed, the RES assigns an average wage to each and forwards the recommendation to the Case Manager. The Case Manager then uses that wage as the worker’s “estimated earning capacity” to calculate ongoing wage-loss supplements or the ELP.

What this means is that a single click inside a database can now determine the financial future of an injured worker.

Anatomy of a Misfit: When ALIS Overshoots Reality

Consider a hypothetical example based on an actual WCB file.

A 57-year-old heavy equipment operator suffers a right knee ligament injury and is left with permanent restrictions: limited bending, squatting, lifting, and climbing. He cannot safely return to heavy equipment work. His experience is exclusively field-based—no supervisory duties, no computer training, no post-secondary education.

The Re-employment Specialist reviews ALIS and identifies “Transportation Manager” as a suitable occupation because it is sedentary and related to transportation. On paper, the role seems logical: same industry, lighter physical demands, good wages.

But a closer look at the ALIS profile shows the cracks:

- Skill Level A, requiring a university degree or equivalent management experience.

- Duties include budgeting, staff supervision, compliance reporting, and logistics software use.

- Average salary: $87,000+ per year.

The worker, of course, has none of these credentials. In the open labour market, he would not even qualify for an interview. Nevertheless, WCB imputes that $87,000 salary as his earning capacity, effectively declaring him employable at a professional managerial level.

His monthly wage-loss top-up is slashed from several thousand dollars to barely over one thousand. The reasoning? “ALIS indicates this occupation is sedentary and within restrictions.”

That single sentence, repeated across hundreds of files, now dictates the outcome of real lives.

The Consequences of ALIS Overreach

1. Inflated Earning Capacity → Reduced Compensation

When WCB imputes high salaries based on managerial or technical roles, workers’ wage-loss benefits are reduced or terminated. The theoretical earnings erase the gap between what the worker used to make and what WCB thinks they can make now.

2. Vocational Disengagement

Many injured workers, confronted with unrealistic job leads, stop participating in re-employment programs altogether. They are asked to pursue careers for which they are neither qualified nor competitive, creating frustration and learned helplessness.

3. Policy Contradiction

Policy 04-04 requires ELP determinations to reflect realistic employability. Using ALIS without field verification violates that standard. It replaces the balance of probabilities test with assumed averages.

4. Loss of Institutional Credibility

WCB’s credibility rests on fairness and evidence-based adjudication. When decisions rely on unverified data instead of employer contact, the system risks appearing arbitrary—especially when the resulting “earning capacity” far exceeds what the worker could ever actually earn.

Why This Matters

At its core, workers’ compensation is not about statistics—it’s about human capacity. Every injury alters not just the body but the worker’s place in the labour market. Accurately measuring that impact requires human judgment, not algorithmic substitution.

The reliance on ALIS reduces nuanced vocational analysis to a spreadsheet exercise. It rewards administrative efficiency at the expense of equity. For the worker, the consequences are not abstract—they are financial, psychological, and lifelong.

How WCB Could Fix It

Re-employment Specialists are not the villains here; they are professionals operating within the constraints of an increasingly digitalized system. Restoring integrity requires both procedural and cultural change.

1. Reintroduce Real-World Employer Outreach

Field verification must once again be the backbone of every LMA. A phone call to an employer provides more truth than a thousand lines of database code.

2. Integrate ALIS as Supplementary, Not Determinative

ALIS should inform, not decide. It can guide RES specialists toward relevant industries but should never replace individualized vocational assessment.

3. Enhance Transparency in ELP Calculations

Workers deserve to see exactly how their “suitable occupations” were chosen and which data sources were used. Transparency breeds accountability.

4. Update Policy Guidance

WCB’s policy manual should explicitly state that ALIS may be used as a reference but not as the sole evidentiary basis for determining earning capacity. The phrase “reasonably attainable” must regain its literal meaning.

A Case Study in Disconnect

Returning to our heavy-equipment operator: after nearly two years out of work and multiple unsuccessful job- search attempts, WCB deemed him “re-employable” as a Transportation Manager earning $87,709 per year.

This is not an outlier—it is emblematic of a broader trend. Across Alberta, injured workers are being told they can earn wages that belong to careers they’ve never trained for, in industries that would never hire them.

By substituting data for diligence, WCB has created what might be called the ALIS illusion—a digital mirage of employability where none exists.

The Wrap: Restoring Reality to Vocational Adjudication

ALIS is not the enemy; misusing it is. As a career-exploration tool, ALIS remains valuable. But when transformed into the linchpin of WCB’s vocational adjudication system, it distorts outcomes and erodes fairness.

Workers deserve a process grounded in what is, not what might be. They deserve specialists who talk to real employers, not just to databases. They deserve earning-capacity determinations that reflect their actual prospects, not the optimistic averages of an occupational index.

Until that balance is restored, the gap between policy and reality will continue to widen—and the injured workers who fall into it will keep paying the price.